An Architect’s Guide to P3s

By Robin G.

Text

By Robin G. Banks, Esq.

Licensed to practice law in Maryland and DC, Robin G. Banks focuses her practice on construction law, representing design professionals and other industry participants in contract drafting and negotiation and design and construction related disputes. She serves as Associate Outside Counsel to the AIA Contract Documents Committee and is an Allied Member of the AIA. Robin received her undergraduate degree in Economics from the University of Delaware, and her law degree from the University of Baltimore.

Summary

Federal, state, and local governments in the United States see Public-Private Partnerships (P3s) as a means to implement critical infrastructure improvements, such as improved public roads, highways, and bridges, and construct municipal improvements, such as courthouses, airports, and higher education residential facilities, when they have no immediate way to fund them. While benefits abound for the public entities under P3s, they also offer architects exciting opportunities.

However, P3s are not right for every project and may be fraught with traps for the architect. When the project is successful, an architect may have a tremendous upside, but with a “problem project,” the architect may face significant practice-threatening risks if he or she fails to adequately evaluate, manage, or price the risks.

The Guide identifies various risks associated with P3s and ways for architects, together with their attorneys and insurance advisors, to manage the risk during the contracting process. Understanding the risks posed by a P3 solicitation and attendant documents is critical to helping ensure that any Teaming Agreement and Design Agreement between a contractor and the architect reflect only the risk that the architectural firm is willing and able to assume.

What are P3s

Federal, state, and local governments in the United States have discovered Public-Private Partnerships, also known as P3s, and love them. They see them as solutions to the problem of needing critical infrastructure improvements, such as improved public roads, highways, and bridges and new and innovative water/wastewater facilities, with having no immediate way to fund them. P3s are also moving, albeit more slowly, towards vertical projects, including higher education residential facilities, airports, courthouses, and prisons, among other municipal buildings. In theory, the system works. Historically, a public entity desiring such improvements relied upon increases in taxes, traditional debt financing (including TIFs), or a (much less likely) budget surplus to fund the improvement. The public entity then proceeded with construction through a design-bid-build or, more recently, a design-build, delivery method. With a P3, the public entity partners with a private entity. The private partner (or developer) designs, builds, and finances the design and construction of the improvement with a combination of private equity and borrowed funds. In some cases, the private partner (or concessionaire) also operates, or operates and maintains, the improvement for a stipulated period of time after completion.

Benefits abound for the public entity under a P3. The public entity obtains much needed financing, without burdening itself or the taxpayers with the tremendous cost of the improvement; it receives an accelerated project delivery; and it transfers risks typically associated with the construction (which often includes existing environmental conditions and differing site conditions, among others), financing, facility management, and lifecycle of the improvement, to the private partner.

P3s also offer architects a variety of exciting opportunities for participation. The architect may serve as a consultant to the public owner or developer/concessionaire, in a like manner to an owner’s consultant on a more “traditional” project. In this capacity, the architect’s potential services range from feasibility studies and environmental assessments, to the development of criteria for the project and bridging designs, to the selection of the contractor and its team, to review and advising on the design to construction administration services. Alternatively, the architect may furnish design services to a contractor, who has contracted with the developer/concessionaire to design and construct the project. In doing so, the architect becomes no more than a “regular” subcontractor to the contractor, rather than an advocate of the owner.[i]

P3s, however, are not right for every project[ii] and are fraught with traps for the unwary participant. Perhaps the most unwary of all is the architect. On a successful project, an architect participating in a P3 may have a tremendous upside, as he or she may earn high fees and gain valuable professional exposure and recognition. However, on a “problem project,” the architect may face significant–practice threatening–risks if he or she failed to adequately evaluate, manage, and price the risks before taking the plunge into the P3. While it may be natural to think that the architect works hand in hand with, and as a partner of, the contractor not only in furnishing a design to bid, and ultimately construct, the project, but to identify areas of concern in the proposed construction agreement and to negotiate terms that reasonably protect all parties–this is not typically how the process works.

In order to win the project, many contractors willingly assume significant design and construction risk and seek to flow all of that risk down to the architect under the guise that (1) the contractor has agreed to be bound by the terms of the contract for design and construction and cannot hold the architect to a “lesser standard,” and (2) the architect is in “complete charge” of the design. Thus, rather than becoming a collaborative partner, the architect becomes a pawn in the contractor’s game of risk-shifting.

In an effort to avoid this result, architects–together with their attorneys and insurance advisors – must take an active role in managing their risk during the contract process. They accomplish this goal by ensuring that the contract documents reflect only the risk that they are willing to assume and that they clearly define the assumptions upon which their services are based. This guide identifies the perils riddled throughout the contract documents at various stages of the architect’s journey through a P3 project and provides architects with suggestions for addressing those risks.

The teaming agreement

Sometimes, a contractor becomes aware of an attractive P3 opportunity through a developer/concessionaire’s solicitation for qualified firms (in a Request for Qualifications or “RFQ”) or proposals (in a Request for Proposals or “RFP”). In other instances, the contractor learns of the opportunity long before its formal advertisement. In either case, the contractor knows that it needs a strong team to win the project. That team includes a qualified design firm to furnish a design, which the contractor will use to generate its bid. The contractor approaches the architect and proposes that they form a team to pursue the opportunity. The execution of an enforceable teaming agreement is critical for this purpose. It ensures the commitment of the contractor and architect to each other and to the opportunity and, in most cases, creates an exclusive relationship between those parties.

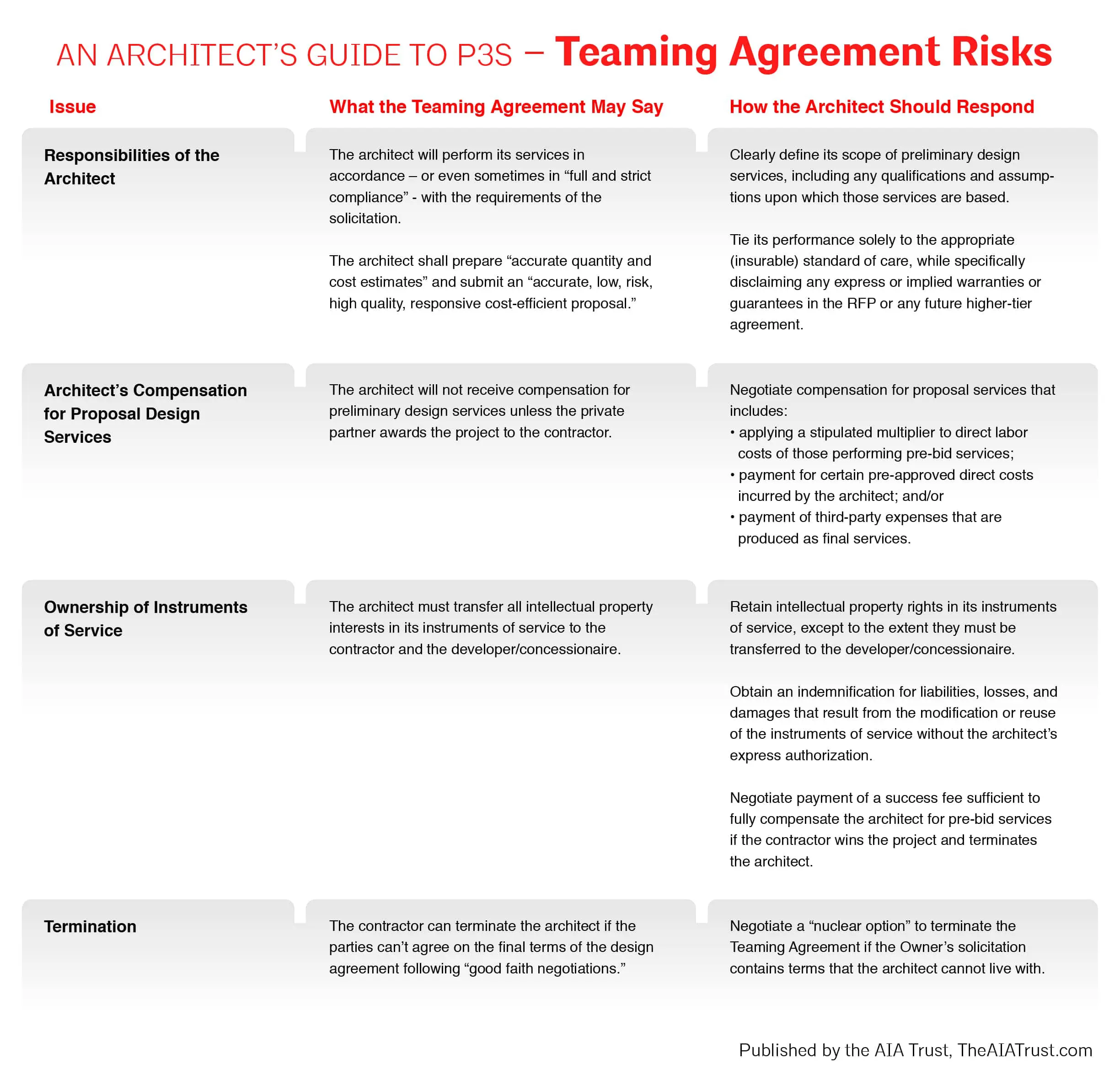

Although contractors and architects may enter into a teaming agreement at any time, they often do so before the private partner issues the RFQ or RFP. At this juncture of the P3, the agreement between the public entity and developer/concessionaire, the arrangements for the developer/concessionaire’s financing for the project, and/or a draft agreement for the design and construction (which would be included in the RFP) likely have not been finalized. As such, the contractor’s obligations vis a vis the project are completely unknown, and this makes the teaming process that much more risky for the architect. The following chart identifies some of the biggest areas of concern and recommendations for modifying the teaming agreement to address those concerns:

The design agreement

Contemporaneous with the negotiation of the Teaming Agreement, the contractor and architect must negotiate the design agreement. This agreement will govern the relationship between the parties in the event the contractor wins the opportunity. It may seem illogical for parties who may not even qualify to submit a bid, or will not be submitting a bid until the future, must substantially negotiate the terms of an agreement that they may never have the opportunity to perform. However, teaming agreements, by their very nature, are agreements to work together in the future. Such agreements often lack clear evidence of the parties’ intent to agree on the material terms of the contract or that the team members intended to be bound by the resultant subcontract. In consequence, courts routinely hold such agreements unenforceable unless they contain clear scope, compensation (or method for determining compensation), and terms and conditions that will govern the parties’ relationship if the contractor wins the opportunity.

While the law requires architects to pre-negotiate the design agreement in order to protect its rights to perform services, if the contractor wins the project, there are significant risks in doing so. As previously indicated, virtually every agreement furnished by a contractor to an architect will seek to protect the contractor from any risk associated with the design. The following chart identifies some of the biggest areas of risk, from both an insurance coverage and business standpoint, and recommendations for modifying the design agreement to address those concerns:

Issuance of the RFP

Once the contractor and architect agree upon the terms of, and execute, the teaming agreement, they must await and/or evaluate the RFP and attendant procurement documents. While the procurement documents often include a sample contract for design and construction of the project, the developer/concessionaire may revise that contract even during the procurement process. At this juncture, the architect should:

- Take an active part in reviewing not only all iterations of the contract for design and construction, but all of the other required submittal documents, to provide input into, and take exceptions to, the practice-jeopardizing terms in the contract that will inevitably flow down to the architect;

- Work closely with the contractor to prepare the proposal response to, ideally, include an insurable standard of care and indemnity for design services;

- Furnish the contractor–for inclusion in the proposal–a narrative that: (1) addresses the basis for design (including, but not limited to, any assumptions made by the architect based upon representations from the public owner and/or developer/concessionaire that the architect relied upon); (2) clarifies that the design is a work in progress (i.e., incomplete); and (3) advises the contractor to anticipate and account for further design development and changes to the design and account for those changes; and

- Line up all (or most) of his or her sub-consultants for the project to ensure coverage of the full design scope, to ensure that the sub-consultants have sufficient insurance coverage and meet any insurance requirements contained in the RFP, and to obtain input on the contract for design and construction and submittal documents.

Acceptance of the contractor’s proposal

Assuming the developer/concessionaire accepts the contractor’s proposal, the contractor and developer/concessionaire then proceed to negotiate the final terms of the design-build contract. Again, the architect should seek an active role in those contract negotiations by:

- reviewing higher tier project documents;

- amending its design proposal to reflect differing risks and responsibilities from its initial proposal;

- ranking its “must have” provisions; and

- knowing when to “cut bait” and not pursue the opportunity if the risk is too great.

Conclusion

On P3 projects, contractors willingly assume significant design and construction risk; they then engage in a game of risk-shifting to all downstream parties. Rather than being merely a pawn in the game, at the mercy of the contractor, an architect must take an active role in managing its risk during the entire teaming and contracting process. The architect should take advantage of its own resources, i.e., in-house or outside legal counsel and insurance advisors, to help ensure that the contract documents reflect only the risk that it is willing and able to assume and clearly define the assumptions upon which its services are based.

Notes:

[i]For a more detailed discussion of the effect of this change on, and policy challenges and implications of, the Architect’s role under a P3, see The American Institute of Architects’, Public-Private Partnerships: What Architects Need to Know.

[ii] For a more detailed discussion about considerations for whether a P3 is “right” for a particular project, see The American Institute of Architects’ Public-Private Partnerships: What Architects Need to Know.

For additional information about P3s, read the AIA Trust article: Ten Things to Know About P3s.

All information on this page is copyrighted by Robin Banks. A license is granted to the AIA Trust and to members of The American Institute of Architects to use the same with permission. The author and the AIA Trust assume no liability for the use of this information by AIA members or by others who by clicking on any of the links above agree to use the same at their sole risk. Any reproduction or use is strictly prohibited.

This information is provided as a member service and neither the author nor the AIA Trust is rendering legal advice. Laws vary by state and member should seek legal counsel or professional advice to evaluate these suggestions and to advise the member on proper risk management tools for each project.