An Architect’s Guide to Using Drones

By Michael J.

Text

By Michael J. Corso, Esq.

Summary

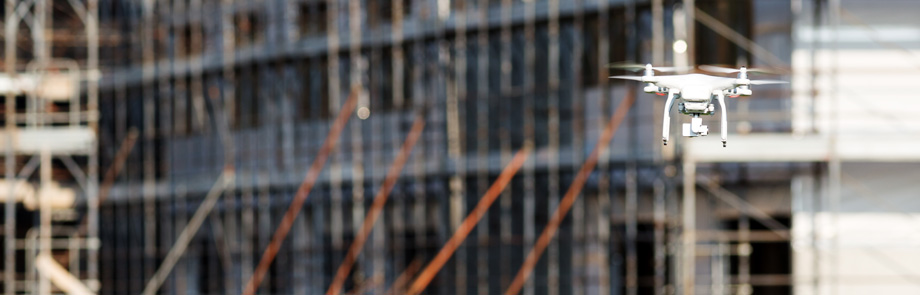

Unmanned flight is not new, nor is aerial photography. Hobbyists have been rigging cameras to model airplanes since long before the word “drone” became commonplace. What is new is the proliferation of mass-produced, inexpensive unmanned aircraft with capabilities that surpass anything previously available to civilians. According to the Consumer Electronics Association, there may have been close to one million new drone owners as of New Year’s Day 2016!

The author’s interest in the growing unmanned aircraft system world (known throughout this paper as drones) stems from flying planes by age 14, a father who was a mechanical engineer for Boeing, his degree in Aerospace Engineering from Purdue University—home to many astronauts, and his service in the United States Air Force with surveillance/manned aircraft reconnaissance as a pilot and engineer, and later as a JAG officer.

This guide focuses on some legal considerations related to the use of drones in a commercial setting, along with liability insurance concerns and considerations about the use of drones within a design professional’s work product and services.

Drones—also called unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or unmanned aerial systems (UAS)—are most simply described as flying devices that do not carry a human pilot. They can be remotely piloted or they can pilot themselves based on pre-programmed instructions. They can be equipped with GPS, on board computers, hardware, electronics, sensors, stabilizers, auto-pilots, servo controllers, and any other equipment the user desires to install. Drones can resemble fixed-wing airplanes but more commonly take the form of quad-copters, that is, rotor-wing aircraft that can take off and land vertically. Most people know that drones can be equipped with infra-red cameras (still and video), license-plate readers, “ladar” (laser radar that generate three-dimensional images and can be seen through trees and foliage), thermal-imaging devices, or even sensors that gather data about weather, temperature, radiation or other environmental conditions. All of this can be used to generate images, recordings or data that design professionals eventually will want to use in their business.

Many in the business world who are interested in UAS operations ask: When can we start making money and using such systems for legitimate business interests? The main problem they face is a legal one: The current Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) stand is a bottleneck for the entrepreneurial energy flooding the drone industry. The most pressing issue presently for UAS operators and the public at large is what uses of UAS are legal, pursuant to both state and federal laws and regulations. The legality of civilian use is quickly evolving through legislation, rule-making and court proceedings.

The airspace above us, and the need to control that which goes through it, is under the jurisdiction of the federal government, more specifically the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). State laws also need to be considered as concerns over safety, privacy and other issues have led many states to introduce legislation that prohibits UAS use. As it relates to state legislation, you need to ascertain any and all state laws and regulations related to drone usage.

ALERT: The federal rules related to drone usage have been happening at a fast pace. These rules apply to people and organizations who want to fly drones for hire or want to use them in their work or in business. The general federal rule is that any commercial operation—even if it is aeronautically identical to a hobbyist operation—is impermissible unless the operator has “special permission” to fly.

Effective August 29, 2016, the FAA has a new small drone rule—formally known as Part 107. Under the new rule, the person actually flying the drone must have a “remote pilot certificate” with a small UAS rating, or be directly supervised with someone with such a certificate. For the certificate, you must either pass an initial aeronautical knowledge test at an FAA-approved knowledge testing center, or have an existing non-student Part 61 pilot certificate. If you are qualifying under the latter provision, you must have completed a flight review in the previous 24 months and must take an FAA UAS online training course.

The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) will conduct a security background check of all remote pilot applications prior to issuance of a certificate. The FAA has posted extensive materials, including a test guide and sample questions, to help you prepare for the knowledge test. You can review the materials by clicking on the “knowledge test prep part 107” button at www.faa.gov/uas. Please see the attached Exhibit A with a three page summary of the Small Unmanned Aircraft Rule (Part 107).

Prior to the latest rule, the FAA created an exemption application process (called a Section 333 Exemption) for getting permission to use a drone commercially. The application or petition for the commercial use exemption must have detailed data on the following:

- Proximity of the operator to the UAS;

- Distance of flight from navigable air space;

- Plans for uncommanded flight deviation;

- Software employed;

- System redundancy; and

- What happens if the device stops or loses communication with the pilot

Five thousand plus exemptions have been approved as of August 29, 2016 and the meaningful conditions to the commercial drone exemptions that have been issued include the following:

- Each operation must have a pilot and observer;

- The pilot must have at least a FAA private pilot certificate and a current medical certificate;

- The drone must also remain in the line of sight at all times of the pilot and observe (It should also be noted that effective December 21, 2015, anyone who owns a small unmanned aircraft of a certain weight must register with the FAA Administration’s UAS Registry before they fly outdoors. See the FAA Rules relating to the details of such a registration).

Section 333 vs. Part 107: What works for you? See attached Exhibit B.

Decision to Operate or Hire Someone to Operate

The design professional first must decide whether to get into the business of operating a drone for commercial use, or hire someone to do the same. The new rule related to small drone usage for commercial purposes is outlined above (also see Exhibit B). Alternatively, there are businesses that exist that have, or are in the process of obtaining, a Section 333 or Part 107 exemption from the FAA to operate a drone for commercial purposes. In hiring such a firm, it is highly recommended that you enter into a written agreement with that sub-consultant; a suggested format for that agreement is attached hereto as Exhibit C. This proposed agreement covers subjects of insurance, indemnity and warranty and permits.

If the design professional desires to actually provide the drone, it is highly recommended that liability insurance for the usage of the same be obtained. Please see the link at www.traversaviation.com/drone-insurance-guide.html or www.drone-insurance.com that discusses the general state of liability insurance for drone operators that exists at the present time.

Summary of Decisions to Be Made:

- To become a FAA authorized operator of a small drone, or to hire an organization that has been so approved;

- If becoming an operator, obtain liability insurance; if hiring someone to perform the drone services, enter into a written sub-consultant agreement with them addressing insurance, indemnity and other issues;

- Check your state and local jurisdiction for any laws related to the civilian use of drone

Disclaimer

All information on this page is copyrighted by Michael J. Corso. A license is granted to the AIA Trust and to members of the American Institute of Architects to use the same with permission. The authors and the AIA Trust assume no liability for the use of this information by AIA members or by others who by clicking on any of the links above agree to use the same at their sole risk. Any reproduction or use is strictly prohibited.

This information is provided as a member service and neither the Author nor the AIA Trust is rendering legal advice. Laws vary by state and member should seek legal counsel or professional advice to evaluate these suggestions and to advise the member on proper risk management tools for each project.

[su_button url=”/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/2017-Guide-to-Using-Drones.pdf” background=”#ffffff” color=”#ff0000″ size=”5″ radius=”square”] Download as PDF [/su_button]

More on Firm Management & Professional Liability

Professional Liability Insurance Database

Professional Liability

Self Assessment Tests (SATs)

Firm Management ▪ Professional Practice

Is Your Firm Eligible for a Premium Credit?

News ▪ January 2009